“The Mile That Never Ends”

They called it the mile. But it wasn’t just a mile.

It was the sound of sneakers slapping asphalt in the early morning. The sting of cold air in your lungs. The awkward silence of classmates watching you struggle through sit-ups while the gym teacher clicked a stopwatch with clinical detachment.

For generations of American children, the Presidential Fitness Test was a rite of passage. A ritual of sweat, shame, and silent competition. And now, in the year 2025, it’s coming back.

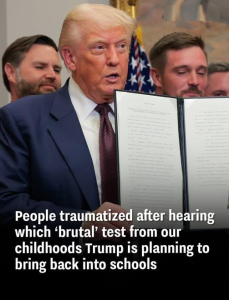

President Donald J. Trump, flanked by athletes and advisors, signed an executive order reviving the test that had once defined physical education in public schools. The mile run. The sit-ups. The shuttle run. The dreaded pull-ups. All of it, resurrected under the banner of Make America Fit Again.

For some, it’s nostalgia. For others, it’s a nightmare.

Maya, now a high school PE teacher in Ohio, remembers the test vividly. “I was ten. I couldn’t do a single pull-up. I cried in front of the whole class,” she says. “Now I’m supposed to administer the same test to my students? I’m torn. I want them to be healthy—but not humiliated.”

The revival is part of a broader initiative led by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., aimed at combating childhood obesity and chronic disease. The statistics are grim: rising rates of diabetes, heart conditions, and sedentary behavior among children. The solution, according to the administration, is discipline, tradition, and measurable performance.

But critics argue that the test is less about health and more about control.

Breanne Fahs, a professor of gender studies, calls it “a reversal of logic.” She points out that while Michelle Obama’s health initiatives focused on nutrition and holistic wellness, Trump’s version leans into competition and physical benchmarks. “Even fit kids struggled with the test,” she says. “It’s not just about ability—it’s about what we’re telling kids their bodies should be.”

In Copperview Elementary School in Utah, the announcement has already stirred debate. Principal Daniel Ashbridge sees potential: “Recess and PE are crucial. If this brings attention back to physical activity, maybe it’s a good thing.” But others worry about the psychological toll. “We’ve worked hard to make PE inclusive,” says Meredith Dolny, a physical education specialist. “Random teams, no last picks, no public rankings. This test could undo all that.”

The original Presidential Fitness Test was born in the 1950s, under President Eisenhower, and popularized by JFK in the 1960s. It was a Cold War-era response to fears that American youth were becoming soft—unfit for military service, unprepared for global competition. Kennedy’s famous essay, The Soft American, warned of a nation losing its vigor.

Trump’s revival echoes that sentiment. “We are building a nation of strong, proud, and unstoppable young Americans,” he declared. “The test is not just about physical strength—it’s about character, competition, and confidence.”

But what does it mean to measure character through push-ups?

For Jamal, a 14-year-old in Detroit, the announcement feels personal. “I’m not fast. I’m not strong. But I’m smart. I write poetry. I help my mom with her business. Why does that count less?” His mother, Denise, worries the test will reinforce harmful stereotypes. “Kids already feel pressure to look a certain way. Now they’ll be graded on it.”

Body image experts warn that standardized fitness tests can exacerbate anxiety and shame. Research shows that concerns about appearance can begin as early as age three. By middle school, many students already internalize negative beliefs about their bodies. A national test, they argue, could deepen those wounds.

Still, some see opportunity.

Coach Ramirez in Texas is optimistic. “If we do it right—if we frame it as personal growth, not competition—it could be powerful. Kids need goals. They need to feel proud of progress.” He’s designing a curriculum that emphasizes improvement over perfection. “It’s not about beating others. It’s about beating yesterday’s version of yourself.”

The new version of the test will include updated metrics and a revamped Presidential Fitness Award. Schools will be encouraged to celebrate participation and effort, not just top scores. The President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition will partner with athletes and educators to promote healthy habits nationwide.

But the cultural undercurrents run deeper.

Vice President J.D. Vance framed the initiative as a response to screen addiction and declining resilience. “Kids spend too much time on their phones. We want them to move, to compete, to grow.” It’s a vision of childhood rooted in grit and discipline—a counterpoint to what some see as a culture of comfort.

And yet, the question remains: who gets left behind?

In rural schools with limited resources, implementing the test may be difficult. In communities where trauma, poverty, or disability shape daily life, the test could feel punitive. Advocates urge flexibility, compassion, and context.

Back in Maya’s gym, the echoes of childhood linger.

She watches her students stretch, laugh, stumble. She sees the ones who hide behind lockers, afraid to be seen. She remembers being one of them.

“I’ll give them the test,” she says. “But I’ll also give them choice. I’ll tell them it’s okay to struggle. That strength isn’t just in muscles—it’s in showing up.”

Because the mile isn’t just a measure of distance.

It’s a metaphor.

For the journey we take through shame and pride, through fear and resilience. For the way we learn to carry our bodies, and our stories, through a world that demands performance.

And maybe, just maybe, the mile can be reclaimed.

Not as a test.

But as a path.