When Reality Breaks: Why the “Musk–Sweeney” Image Feels Wrong to the Eye

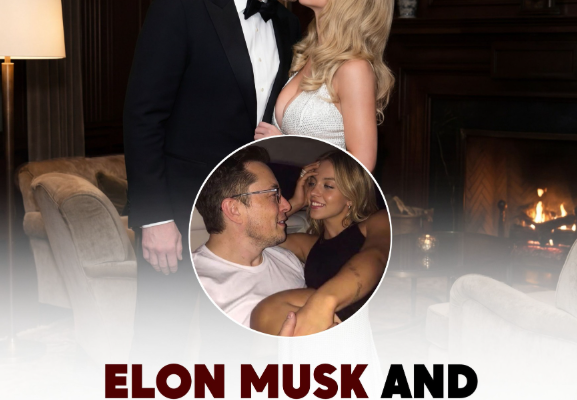

At first glance, the image of Elon Musk and Sydney Sweeney in an intimate pose appears convincing. Two famous faces, close together, caught in what seems like a private moment. But the longer you look, the more something feels off. It isn’t just a vague sense of discomfort—it’s the human brain detecting inconsistencies in anatomy, light, and spatial logic. These small errors are exactly where manipulated or AI-generated images tend to reveal themselves.

One of the most obvious problems lies in the anatomy where their faces meet. In real human interaction, when two people lean in close—especially cheek to cheek or mouth to mouth—the skin compresses, contours shift, and subtle asymmetries appear. Cheeks flatten slightly, noses bend minutely, and the soft tissue responds to pressure. In the Musk–Sweeney image, however, that zone is blurred and undefined. Instead of showing realistic deformation, the faces seem to fade into each other, as if the software couldn’t decide where one person ends and the other begins. This lack of structural clarity is a hallmark of synthetic imagery.

Human vision is extremely good at reading faces. We evolved to notice tiny deviations in expression, proportion, and contact because they carry social meaning. When an image fails to follow the rules of real anatomy, the brain flags it as “wrong,” even if we can’t immediately explain why. The blurred contact point between Musk and Sweeney doesn’t behave like real skin interacting with real skin. It behaves like pixels being averaged together.

Musk’s jawline is another giveaway. In photographs, jawlines have crisp edges defined by bone structure, muscle tension, and shadow. Even in soft lighting, there’s usually a clear boundary where the face ends and the neck or background begins. In this image, Musk’s jawline seems strangely softened, as though it has been airbrushed or partially dissolved into the surrounding tones. Instead of a firm anatomical anchor, it looks like a suggestion of a jaw rather than a real one. This often happens when an AI system generates a face by blending many examples together—it creates something that looks plausible at a distance but collapses under close inspection.

Lighting is perhaps the most powerful clue that something is wrong. Light in real life is consistent. If two people are in the same environment, the direction, color, and intensity of light should match on both of them. Shadows should fall in the same direction. Highlights should appear on similar planes of the face. In the Musk–Sweeney image, Sweeney’s hair seems to catch light from a source that doesn’t quite match the light on Musk’s face. Her hair glows in a way that feels studio-lit, while Musk’s skin tones suggest a different, flatter illumination. It’s as if they were photographed in two different places and then digitally merged.

Hair is especially hard for AI and compositing tools to get right because it interacts with light in complex ways. Real hair reflects, absorbs, and scatters light depending on its color, thickness, and texture. When the lighting on hair doesn’t match the environment, it can look pasted on—too shiny, too matte, or glowing unnaturally. In this case, Sweeney’s hair doesn’t seem to belong to the same space as Musk’s face. The physics of light simply don’t line up.

Another issue is depth and focus. In real photography, when two people are close together, the camera’s depth of field usually puts both faces in roughly the same focus plane. If one face is sharp, the other should be similarly sharp unless there’s a strong artistic reason otherwise. In manipulated or AI-generated images, you often see uneven sharpness—one part of the image looks crisp while another looks smeared or painterly. In this image, the region where their faces meet lacks the kind of micro-detail you’d expect in a real high-resolution photograph. Instead of pores, fine hairs, and natural texture, you see a smooth, ambiguous blend.

The brain is also sensitive to emotional and physical realism. When two people are close, their body language, eye direction, and muscle tension should tell a coherent story. Are they leaning in? Are their eyes focused on each other? Are their expressions aligned with the moment? In this image, the emotional logic feels off. The faces are close, but the subtle cues that usually accompany intimacy—slight smiles, softened eyelids, micro-expressions—don’t quite land. It’s like the image understands the idea of closeness without fully capturing the reality of it.

All of these problems add up to what many people describe as the “uncanny” feeling of AI imagery. It’s not that the image looks obviously fake in a cartoonish way. It’s that it looks almost real, but not quite. The anatomy is nearly right, the lighting is almost consistent, and the emotions are vaguely appropriate. But the small failures accumulate, and the brain can’t ignore them.

This matters because images like this often circulate online without context. When people see two celebrities together in a convincing pose, they may assume it’s real and start building stories around it. Rumors spread. Reputations get tangled in fiction. The technical flaws—blurred anatomy, mismatched lighting, softened jawlines—become important tools for media literacy. Learning to see them is a way of protecting ourselves from visual misinformation.

In the end, the Musk–Sweeney image isn’t undone by one single mistake. It’s undone by a pattern of subtle inconsistencies: the way their faces merge without proper structure, the way Musk’s jawline lacks firm definition, and the way Sweeney’s hair catches light that doesn’t belong to the same world as Musk’s skin. These aren’t artistic choices. They’re technical failures of synthesis.

The human eye, guided by millions of years of evolution, knows what real interaction looks like. And when an image violates those rules—when skin doesn’t compress, light doesn’t agree, and faces don’t occupy the same physical space—we feel it instantly. Even before we can explain it, we know: something here isn’t real