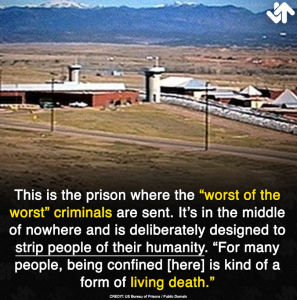

“Realities of Daily Life in Florence ADX Supermax Prison”

Officially known as the United States Penitentiary Administrative Maximum Facility — and unofficially as the “Alcatraz of the Rockies” — ADX Florence sits in the high desert of Colorado, surrounded by razor wire, watchtowers, and miles of nothingness. It’s home to some of the most dangerous and high-profile inmates in America, including terrorists, organized crime leaders, spies, and serial killers.

It’s not just a prison — it’s a machine built for total control. And for the men inside, daily life is a stripped-down, highly regimented existence where human contact is almost nonexistent and every moment is managed down to the minute.

The 7×12 Cell — Your Entire World

Each inmate spends roughly 23 hours a day inside a cell measuring about 7 feet by 12 feet. The walls are solid concrete, the bed is a poured concrete slab with a thin mattress, and the furniture — a desk, stool, and shelf — is made from the same unyielding material. Even the sink and toilet are stainless steel and tamper-proof.

The window, a 4-inch-wide slit angled toward the sky, offers no view of the horizon — only a slice of daylight and a patch of clouds. This design means an inmate can’t see guards moving outside, other inmates, or even the fences.

Many prisoners say the cell feels less like a room and more like a concrete box built to erase the outside world.

The Strict Routine

Life here runs on an unchanging schedule. Wake-up comes early, with lights on around 5:30 a.m. Breakfast is slid through a secure slot in the steel door. Meals are eaten alone.

Daily life follows a predictable loop:

-

Breakfast — delivered to the cell.

-

Morning count — guards visually confirm each inmate’s presence.

-

Lunch — again, in the cell.

-

Recreation — one hour, alone, in a small outdoor cage or an indoor concrete pen.

-

Dinner — the day’s final meal.

-

Lights out — generally around 9 p.m., though the cell is never completely dark due to security lighting.

Everything happens in silence, except for the occasional muffled voice from a distant cell.

Isolation as a Way of Life

ADX is built for single-cell housing. Most prisoners have no cellmate, no communal dining, and no group recreation. The prison’s philosophy is simple: by removing the possibility of inmate-to-inmate interaction, you remove the possibility of violence, escapes, and influence-building.

Communication between inmates is limited to shouting through walls or talking into the drain in the floor. Even this can lead to disciplinary action if guards believe messages are being passed.

The psychological effects of this isolation are profound. Some inmates adapt by developing strict personal routines — reading, writing letters, exercising in their cells. Others deteriorate, reporting hallucinations, depression, and paranoia.

Recreation: The “Concrete Dog Run”

Recreation time happens in what many inmates call a “dog run” — a narrow outdoor enclosure surrounded by tall concrete walls and topped with mesh. There’s no direct contact with other inmates, and the view is limited to a patch of open sky.

For some, it’s the only time they feel fresh air on their skin. Inmates can pace, do push-ups, or simply stand still, soaking in the daylight before returning to their cell.

The Food

Meals are basic but nutritionally adequate — think processed meats, beans, rice, and bread. If an inmate breaks rules, they can be put on a “restricted diet,” often nicknamed “the loaf,” a dense, baked mixture of grains and vegetables designed to be bland and unappealing.

Food is served through a slot in the door, and all utensils are plastic. Everything is portion-controlled.

Communication With the Outside

Contact with the outside world is limited. Prisoners can write letters, but these are monitored, read, and censored by staff. Phone calls are rare — often only one per month — and must be approved and monitored.

Family visits, when allowed, happen behind glass partitions, with no physical contact. The prisoner and visitor speak through a telephone handset while guards watch closely.

Security Measures at Every Level

ADX Florence is built on a philosophy of “control through design.” Cells, corridors, and recreation areas are positioned so guards never need to be physically close to inmates. Every door, light, and camera is electronically controlled.

Movement inside the prison is highly restricted. When an inmate leaves their cell, even for medical visits or showers, they are shackled at the wrists, waist, and ankles. Multiple officers escort them, and the path is cleared before they move.

Programs and “Step-Down” Units

While ADX is known for its isolation, there is a “step-down” program for inmates who follow the rules and demonstrate they can be managed with fewer restrictions. This process can take years and involves gradually increasing privileges — such as more out-of-cell time, access to limited group recreation, and eventually transfer to a less restrictive facility.

However, not everyone qualifies. Some inmates are considered too dangerous or too high-profile to ever leave ADX’s most secure units.

Mental Health and the Human Cost

ADX has long been criticized for the mental health impact of its extreme isolation. Former inmates and psychologists have described the toll it takes: insomnia, depression, self-harm, and in some cases, psychosis.

The prison does have mental health services, but critics argue that the design of ADX itself makes treatment challenging. Therapy sessions, when they happen, often take place through a door slot or via video conference, not face-to-face in a shared room.

High-Profile Inmates

Over the years, ADX has housed some of the most infamous figures in modern history:

-

Terry Nichols, Oklahoma City bombing conspirator.

-

Ramzi Yousef, mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

-

Richard Reid, the “shoe bomber.”

-

Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, Mexican drug cartel leader.

They serve their sentences largely in obscurity, rarely seen or heard from publicly after entering the facility.

Why ADX Exists

ADX Florence was opened in 1994 as the federal government’s answer to violent incidents in other prisons. It was designed to hold inmates deemed too dangerous for standard maximum-security facilities — those who had assaulted guards, killed other inmates, or posed extreme escape risks.

Its mission is simple: prevent escape, prevent violence, and maintain control. And by those measures, it has largely succeeded. No one has ever escaped.

The Reality

For the men inside, daily life at ADX Florence is a controlled loop of confinement, silence, and strict routine. Days blur together. Contact is minimal. Time feels both endless and irrelevant.

Critics argue it’s a form of slow psychological erosion — a punishment that goes beyond incarceration into near-total sensory deprivation. Supporters say it’s a necessary measure for the most dangerous individuals in the federal system.

Either way, ADX Florence is unlike any other prison in America. It’s not just about keeping people in. It’s about removing them from the world entirely — physically, socially, and, some argue, spiritually.