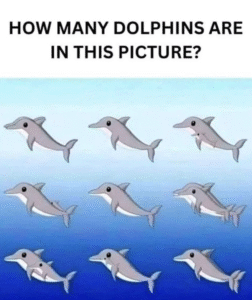

The image in question—often used as a viral optical illusion—asks a deceptively simple question: How many dolphins can you spot? At first glance, most people might say one or two. Perhaps they see a pair of dolphins leaping joyfully from the sea, their curved backs slicing through the ocean spray. But upon closer inspection, something fascinating begins to happen: more and more dolphins seem to appear, hidden cleverly in the lines and negative space of the image.

This type of visual puzzle plays with human perception. Our brains are wired to identify the most obvious objects first—the largest figures, the ones in the foreground, the ones with the highest contrast. However, the hidden dolphins are smaller, subtler, sometimes camouflaged within the bodies of other dolphins, waves, or even the sky.

Some versions of this image contain nine to thirteen dolphins, all layered and interwoven like a visual game of hide-and-seek. A tail here, a dorsal fin there. One might be cleverly disguised in the curve of another’s body. Another might be peeking out from what first appeared to be a splash of water or a shadow in the waves.

Psychologically, these puzzles test more than just visual acuity—they reveal how our brains prioritize information. Some people see all the dolphins almost instantly. Others struggle to spot more than three. Children, interestingly, often do better at these kinds of illusions than adults. Why? Because they’re less likely to impose meaning onto ambiguous shapes. While an adult might look at a curve and interpret it as part of a fish or a boat, a child might more readily see a hidden animal without overthinking it.

The dolphin illusion is also often used to illustrate how perception is influenced by expectation. If someone tells you there are “more than ten dolphins,” your brain switches into detective mode. You begin to scan the image in sections, looking for shapes that break the pattern. Suddenly, what seemed like a swirl of foam becomes the nose of a dolphin. A shadow becomes a fin. Your entire understanding of the image shifts.

There’s also a metaphorical layer to this puzzle. The dolphins represent the unseen parts of life: the details we overlook, the beauty that hides in plain sight, the joy in pausing and looking closer. In a world dominated by speed and surface impressions, this picture asks us to slow down. To study. To question our initial reactions. To dig beneath what’s obvious.

So, how many dolphins can you see? Five? Nine? Maybe even thirteen? There may not be one correct answer, depending on the version of the image. But the true value lies not in the number itself, but in the process of looking—closely, curiously, and with an open mind.

In the end, the image becomes more than a puzzle. It becomes a reminder that life is full of hidden wonders, waiting to be spotted—if only we take the time to truly look.