Canada’s Secret Weapon Against Wildlife Deaths: Bridges You Won’t Believe Exist

Canada, a land celebrated for its breathtaking landscapes, vast forests, and incredible wildlife diversity, is also home to one of the most innovative solutions to a growing problem: animal-vehicle collisions. Each year, thousands of animals—moose, deer, elk, bears, and even smaller mammals—lose their lives on highways that cut through their natural habitats. The cost is not only ecological but also economic, with accidents leading to millions of dollars in damages and, tragically, human injuries and deaths.

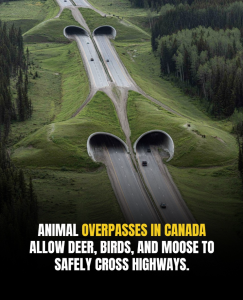

To address this, Canada has quietly invested in an ingenious yet surprisingly simple concept: wildlife overpasses and underpasses. These structures—essentially bridges and tunnels designed exclusively for animals—are saving countless lives, both animal and human. Many people are astonished when they first see these green, tree-covered bridges stretching across busy highways. They look almost surreal, like something out of a futuristic eco-city. But they’re real, they’re working, and they might just be Canada’s secret weapon in protecting biodiversity.

The Problem of Wildlife Collisions

Canada is home to some of the world’s largest land mammals. Moose, for example, can weigh over 600 kilograms. When vehicles collide with such animals, the results are devastating. Highways like the Trans-Canada cut directly through migration routes and feeding grounds, forcing wildlife into dangerous interactions with traffic.

Statistics reveal the scale of the problem: in Alberta alone, an estimated 6,000 large animal collisions occur every year. Across the country, the figure climbs into tens of thousands annually. Beyond the loss of wildlife, these incidents cause injuries, fatalities, and millions in insurance claims. For decades, the challenge seemed inescapable—roads are necessary for human travel, but they fragment and endanger animal habitats.

The Birth of the Wildlife Bridge

The idea of wildlife crossings isn’t new. Europe pioneered some versions in the 20th century, but Canada took the concept to a new level. Banff National Park in Alberta became a global testing ground for this approach. When the Trans-Canada Highway was expanded through the park, engineers and ecologists worked together to design crossings that would reconnect animal habitats.

The results were groundbreaking. Today, Banff boasts more than 40 wildlife crossings—sixteen overpasses and dozens of underpasses—making it the most extensive system of its kind in the world. These crossings are not just functional; they’re works of ecological engineering. Planted with native trees, shrubs, and grasses, the overpasses mimic natural habitats, encouraging even cautious animals to use them.

How Animals Learned to Use the Bridges

Skeptics once doubted whether animals would understand or trust these structures. Would a bear really walk across a man-made bridge instead of just wandering across the road? But decades of monitoring with motion-sensor cameras and tracking devices have provided a resounding “yes.”

Grizzly bears, black bears, wolves, cougars, deer, elk, moose, lynx, and even smaller species like martens and porcupines have all been recorded using these crossings. Some animals were hesitant at first, but over time they adapted. Mothers now teach their young to use the overpasses, passing down a culture of safety through generations.

What’s even more remarkable is the sheer scale of success. Since their installation, wildlife collisions in Banff National Park have dropped by more than 80%. For certain species, the reduction is even higher. These results are unmatched anywhere else in the world and have made Canada a leader in wildlife conservation innovation.

Engineering the Natural World

Wildlife bridges are not simple overpasses. They are feats of design, requiring collaboration between engineers, landscape architects, and wildlife biologists. Each bridge must be carefully tailored to local ecosystems. The width, slope, vegetation, and even soil type are chosen to make the crossing as natural and inviting as possible.

Underpasses, too, are designed with animal behavior in mind. For instance, deer prefer wide, open underpasses, while smaller mammals and amphibians may use narrower, darker tunnels. Some crossings even incorporate streams to allow fish and aquatic life to migrate safely.

To ensure effectiveness, scientists monitor the crossings with cameras and motion detectors. The data not only proves their success but also helps refine designs for future projects.

The Human Benefits

While the most obvious beneficiaries are animals, humans gain enormously from these structures as well. Fewer wildlife collisions mean fewer accidents, fewer injuries, and fewer fatalities. Insurance companies, transportation agencies, and taxpayers save money by avoiding costly repairs and emergency responses.

The crossings also contribute to Canada’s reputation as a country that values sustainability. They represent a rare win-win scenario: infrastructure that supports human mobility while respecting the natural world.

Expanding Beyond Banff

The success in Banff has inspired similar projects across Canada. In British Columbia, wildlife overpasses have been built to protect populations of endangered species like the mountain caribou. Ontario has installed turtle tunnels beneath highways to save threatened reptile species. Quebec has created moose underpasses along dangerous stretches of highway where collisions were once routine.

These initiatives are not limited to national parks—they’re spreading into provincial projects and even municipal planning. Cities are beginning to recognize that urban wildlife, from foxes to frogs, also benefit from safe crossings.

Global Inspiration

Canada’s wildlife bridges have captured international attention. Countries such as the United States, the Netherlands, and Australia are studying the Canadian model to adapt it to their own landscapes. California recently broke ground on what will be the world’s largest wildlife bridge, modeled after those in Banff.

In this way, Canada has quietly become a global leader, showing that coexistence between infrastructure and wildlife is not only possible but highly effective.

The Symbolism of the Bridges

Beyond their practical benefits, these crossings carry symbolic weight. They remind us that human progress doesn’t have to come at the expense of nature. By investing in wildlife bridges, Canada acknowledges that the natural world is not an obstacle to be conquered but a partner to be respected.

They also stand as physical embodiments of connection—between species, between ecosystems, and between human society and the planet that sustains it.

Challenges Ahead

Of course, wildlife bridges are not without challenges. They are expensive, often costing millions of dollars each. Securing funding can be a hurdle, especially when budgets are tight. Some critics argue that the money could be better spent elsewhere.

However, when weighed against the costs of collisions—medical bills, insurance claims, lost animal populations, and human lives—the investment makes sense. Moreover, as designs become more common, construction costs are gradually decreasing.

Another challenge is ensuring that the bridges are placed in the right locations. Careful ecological studies are needed to determine migration routes and high-risk crossing points. Without this data, even the best-designed bridge may go unused.

Looking to the Future

As climate change and urban development continue to fragment habitats, the need for wildlife crossings will only grow. Species will be forced to migrate to new areas in search of food, water, and cooler climates, increasing the risk of dangerous road encounters. Wildlife bridges and underpasses will be essential tools in mitigating these risks.

Canada is already considering expansions of its programs, incorporating new technologies like AI-powered monitoring systems to track animal usage in real time. The hope is that one day, these crossings won’t be seen as “special projects” but as standard features of road construction—just as guardrails and traffic lights are today.

Conclusion

Canada’s wildlife bridges may seem like something out of science fiction at first glance—grassy highways for animals arching above roaring traffic—but they are very real, and they are saving lives every day. They represent a blend of ingenuity, compassion, and respect for the natural world.

Far from being just a quirky Canadian experiment, they are proof that human infrastructure can adapt to wildlife, not just the other way around. In a world where development often threatens ecosystems, Canada has shown a path forward: build bridges, not barriers.

In doing so, the country has given the world a secret weapon against one of the hidden dangers of modern life—a model of coexistence that future generations, human and animal alike, will depend on.