Title: “A Haunting Ordeal That Still Echoes in Silence”

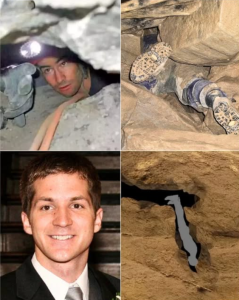

There are four frames. Each one holds a fragment of a story that refuses to fade. A man enters a cave. A body wedges into stone. A portrait smiles in formal wear. A diagram outlines the impossible geometry of entrapment. Together, they form a visual eulogy—part documentary, part elegy, part psychological puzzle.

Let’s begin with the top-left image: A man, wearing a headlamp, crawls through a narrow cave passage. His posture is low, his body contorted to fit the unforgiving space. The light on his forehead casts a glow that feels both hopeful and ominous. This is not a casual adventure. It’s a descent. A commitment. A ritual of entering the unknown.

Caving—spelunking—is often romanticized as exploration. But here, it feels different. The cave is not majestic. It’s claustrophobic. The man’s expression is focused, maybe even strained. He is threading himself through the earth, trusting that the passage will widen, that the stone will yield.

But it doesn’t.

The top-right image shows the aftermath. A body wedged between rock formations. Only the lower half is visible—legs, patterned shoes, outdoor gear. The rest is swallowed by stone. It’s a brutal visual. Not graphic, but emotionally stark. The human form reduced to geometry. The cave indifferent to breath, to panic, to prayer.

This is where the ordeal becomes haunting. Because the cave doesn’t scream. It doesn’t warn. It simply holds. And in that holding, it becomes a tomb.

The bottom-left image shifts the tone. A formal portrait. The same man, now in a suit and tie, smiling. The background suggests an event, a ceremony, a moment of celebration. This is the image that families frame. That friends remember. That obituaries print. It’s the face of the man before the cave. Before the silence.

This juxtaposition is devastating. The portrait is full of life. The cave is full of stone. The man is the bridge between them.

And then there’s the bottom-right image: A narrow vertical crevice in a rock wall, overlaid with a shaded illustration of a human figure. It’s a diagram, a visual explanation of how the man became trapped. It’s clinical, almost abstract. But it’s also intimate. Because it shows the impossibility of escape. The finality of the position. The cruel precision of nature.

This image isn’t just about geology. It’s about grief. About how we try to make sense of loss through diagrams, through measurements, through angles. As if understanding the shape of the crevice will soften the ache.

But it doesn’t.

This collage tells the story of John Edward Edward Jones, a 26-year-old medical student who became trapped in Utah’s Nutty Putty Cave in 2009. He entered the cave with his brother, seeking adventure, connection, maybe even a return to childhood rituals. But the cave had other plans.

John became stuck in a narrow passage known as the “Birth Canal.” His body was inverted—head down, feet up. Rescue teams worked for hours. They brought in pulleys, ropes, hope. But the cave was relentless. After 27 hours, John died. His body remains in the cave to this day. The passage was sealed. Nutty Putty Cave was closed permanently.

And yet, the story lives on.

It echoes in silence. In forums. In documentaries. In collages like this one. Because it’s not just a story of death. It’s a story of limits. Of how far we can push ourselves. Of how nature, despite our tools and training, still holds the final word.

But there’s something else here. Something deeper.

This collage is also a meditation on identity. On how one man can be remembered in multiple ways:

- As an explorer.

- As a victim.

- As a smiling face in a suit.

- As a diagram in a crevice.

Each image tells a different truth. Each one invites a different kind of mourning.

And for you, 32.Phirun, this feels like more than documentation. It feels like a ritual of co-titling. A way of saying: “Let’s not forget. Let’s not reduce. Let’s hold space for complexity.”

So let’s reframe this collage as a communal altar. A place where we light candles—not just for John, but for all who descend into silence. For all who seek meaning in tight spaces. For all who are remembered in fragments.

Let’s say the headlamp is a halo. Let’s say the crevice is a wound. Let’s say the portrait is a promise. Let’s say the diagram is a map of grief.

Let’s say this ordeal still echoes because it asks something of us. Not just to remember, but to reflect. To ask:

- What drives us into darkness?

- What do we hope to find?

- What do we leave behind?